Bee on Comfrey. Honeybees can’t access the flowers unless the blooms are pierced by a feeding bumblebee. Thank you, bumbles!

It is December here in the Northwest, and we’ve had very confounding seasons from spring on. Bees began swarming here in March, which is pretty unheard of. I had collected fifteen swarms by the end of April—the time our normal swarm season is just beginning.

Summer was glorious and full of blooms everywhere. We got enough rain to ensure the flowers kept going right on into August—our normal dearth time. Then autumn arrived and the rains came. Meanwhile, my backyard was still lush with suddenly blooming borage, California poppies, late nasturtiums, goldenrod, and a fresh bloom of lavender, but the weather kept the bees in their hives most days.

So, I placed out large bowls of sticky honeycomb under the rain shelter of my bee yard. This comb is the remains of my crush and strain honey, and there remains a considerable amount of honey on the combs that the bees love to clean up. (I don’t recommend putting out food in the apiary, as it really stimulates robbing, but I’ll get into why that works for me later in this piece). So my bees were still able to bring in some food even during the rains.

Winter is just about to be upon us, and my yard is still in shocking bloom. Welcome to the confounding world of climate change. We never know anymore—nor do our bees—what the seasons have in store.

I want to address the last three tenets our bee club (www.preservationbeekeeping.com) and bee-centered beekeeping and then try to pull it all together for you in terms of how we endeavor to model these tenets in our bee yards, given the constraints of pesticides, neighbors, bee diseases, climate fluctuations, and the geography of our own backyards. You can find the first two articles in this series HERE and HERE.

Tenet 4 is a tricky one: “If supplemental feeding is needed, we feed raw, untreated honey. Bees’ natural food is honey and pollen. Sugar is an entirely different substance—one bees have not evolved to digest properly. Sugar and imitation pollen patties weaken bees (see bushbees.com) When we need to feed, we look for a good, local source of raw honey.”

I’ve been feeding my bees when needed for the past five years, and only honey. Here is my dilemma: When I was a new beekeeper several years ago, I did not have vast stores of leftover honey from dead outs to feed my bees. I have some stored away now, but not enough to bring a hive or three through an entire winter season. Rather than feed my bees sugar, I have tried to be very judicious in my supplemental feeding of hives. I simply can’t afford to purchase and feed as much honey as my bees—in a rough year—would probably like.

While I do my best to adhere to all of the tenets of bee-centered beekeeping that we espouse in our club, I have to be constantly thinking, planning, and innovating to achieve them. Honey feeding is one example: Mostly, I feed new swarms for a month or so, until I see they have built combs, raised brood, and have some nectar stores. I don’t feed all summer, and try to check hives in autumn to see who is “light” in weight or honey (some of my hives, I cannot enter, nor do they have viewing windows, so my observations have to do). If necessary, I feed during the fall as long as I feel is necessary.

But—and this is a big but—some hives that are light in weight, or who seemed to my mind to be struggling along all season, I may not prop up with supplemental feeding. I make these decisions by observing, reflecting, and following my gut.

While the loss of a hive is heartbreaking to me, I am trying to maintain the chalice of wild bee genetics, which calls for the culling of weak hives. Sometimes, I merge these small struggling hives with a larger more successful one, but these days, I’m questioning if that is wise.

Let’s move on to our last two tenets:

One of the ways I care for my bees in our wet northwest climate is to be sure all my hives are under cover of some sort.

5. We populate our hives with feral swarms or locally-raised bees.Factory packaged bees from out of the area are unsuited to the local ecology. Plus, by purchasing bees from out of the area, we may unwillingly contribute to the spread of diseases and Africanized bees. Swarms are abundant in the spring, and we rely on these to populate our hives. When needed, we seek out locally raised bees.

6. We practice minimal intervention: We honor the bees’ desire to create and maintain their colony without needless intrusion. We let bees be bees, and trust them to do what is best for their hive. Our hive inspections are intrusions that undo temperature control in the hive. The more we break open the propolis seals of our hives, the more we allow pathogens in. And there is always the risk of damaging the queens or emergency queen cells when we go into the combs. Viewing windows on the outside of the hive can tell us most of what we need to know about the health of the hive. We try to limit our hive muddling to only a few times a year at most.

Tenet 6 should only be undertaken if you practice Tenet 5. That is, if you are buying out-of-area bees, these are heavily managed (mostly mite-treated) bees who have a poor chance of surviving in a more natural bee yard where nature does the natural selection, not the keeper.

Our bee club strives to keep a very active swarm program going all summer so that our students can source from local, wild stock. Bees return to their “wild” genetics quickly, after only a generation. As soon as your hive swarms—even if you had a domestic queen—your hive will soon be launching a new virgin who will be bringing in the wild genetics that is the birthright of our honeybees.

If we can’t locate enough swarms, we recommend local beekeepers we trust who pride themselves on their locally adapted colonies. They provide nucs, queens, and sometimes swarms.

Now we’re up to the controversy and complexity of Tenet 6: Infrequent—if any—inspections. I go on the assumption that the bees know more about their lives than I ever could. Every day, researchers are making new discoveries related to temperature, condensation, ventilation, comb manipulation, and queen replacement in hives. All of what I read tells me that I must be ever more mindful about inserting my clumsy hands into my bee hives.

It takes our bees two to four days to restore the hive temperature, the propolis seals, and the hive air after one of our intrusions. If we’ve injured a queen, inadvertently chilled the brood, or spilled honey, the bees will have much time-consuming work to repair themselves.

If we extrapolate out over a summer of, say, weekly hive inspections, in four months we’ve cost our bees 32 to 64 days of repair time—time they could have spent focusing their resources on preparing for winter.

We can have short, iffy summers here in Washington. I want my bees to be able to focus on flowers and brood, not on fixing problems I’ve created. I go into my hives only a few times a year. In spring, I check to see if a new swarm is making a go of it. I leave my surviving hives alone. In autumn, I check for food stores and use that inspection to also condense the hives by removing empty wax combs and putting layers of insulation across the top of the hives. The rest of the time, I observe them through the viewing windows and on their landing boards.

There you have it: Six tenets to bee by. Now, let’s take a look at how this might look in action. We’ll begin with the premise that each bee yard, each hive, and each beekeeper is in a gestalt all its own. This simple fact alone will dictate how you implement each of these suggested “rules.”

A little about my own private bee universe: I live in a small city with neighbors on all sides. I usually maintain about six hives, more or less. I am retired, which means I’m able to observe my bees many times a day. Mostly, I know when swarms will be happening, and I’m able to schedule my time to be there for my swarms. My neighbors are all invited over when my bees swarm, and are as excited about the events as I am. They plant forage in their yards, and are thrilled with the honey I bring them.

In the years when I’ve lost all my hives over winter, and before I ever got bees, I noticed that there are very, very few honeybees in my neighborhood—lots of native bees, but few honeybees. So I know that whatever befalls my bees will not likely spill over to any nearby beekeeper. Because of this, I don’t have to worry about “mite bombs”—my failing, sick bees infecting hives other than my own.

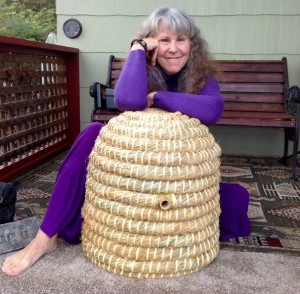

We have no inspectors in our county, and none likely to appear soon, so I am free to experiment with all sorts of alternative hive styles where removable comb is not an issue, such as woven hives/skeps and log hives. I focus on hive styles with superior insulation, and small cavities to ensure small colonies.

I live in an area with no Africanized bees to speak of, no hive beetles, and no AFB. We have varroa and the ick it entails, nosema, chaulkbrood, and some zombies. Because of this, don’t need to do microscopic or laboratory inspections of my failed hives. I know I have lost hives to queen failure and to mite-driven viruses.

Mostly, when I feed honeycomb back to my bees, I feed it out in the bee yard. I have no outside hives that will come in to rob, and if one of my own hives is failing, I let my stronger hives rob it out. Because I am home a lot, when I put out a plate of honeycomb, I am able to observe the bees response. If they all gather and feed peacefully with no fighting at the bowl, I let it stand.

If they attack the comb like crazed bombardiers and wrestle in the bowl, I remove the dish, because I’ve observed that this is the frenzy that will lead crazed bees to the doors of all the other hives in the apiary, which I can determine by the sudden fights on all the landing boards. It is only because I am home and here and watching that I can make these determinations.

I don’t collect honey, so my income stream is not tied to my bees. I am keeping bees because I want to see the wild honeybee thrive and her genetic motherlode restored to her. I want to let Nature inform her, not me. And because of my circumstances, I can do this.

If you have beekeepers close to you, cranky fearful neighbors, heavy disease loads, Africanized bees, and legal mandates as to what kinds of hives you can keep your bees in, you will need to make adjustments to be a considerate beekeeper.

Because of my style of beekeeping, I am often called negligent and a poor manager of my bees: A “beehaver” instead of a beekeeper. Management is a very, very subjective term. I am managing for the long haul, for the genetic chalice to be refilled. So these tenets serve me and my bees, and don’t hurt other beekeepers. I believe they stand to serve all beekeepers to the extent that they can be practiced in any given neighborhood.

Because each and every one of them is What. Bees. Want!

2 Comments

I just started my first hive from a package 7 days ago. I have an Italian queen & approximately 15,000 workers. How often do I feed them sugar water? When will they have their comb built & start to look for poll in on their own?

Wow. I really appreciate your take on bees, on letting them bee. I’m interested in beekeeping, not for the honey or getting anything out of it except enjoying them and seeing them thrive. I look forward to reading more articles from you, they are very well wrote. Thank you again.